Congratulations Maj Dang Trong, newly titled PhD

On 8 December, Maj Dang Trong, Senior Adviser at Nordic Energy Research, defended her PhD on consumer engagement in energy markets – its role, development, and impact on network tariffs…

On 8 December, Maj Dang Trong, Senior Adviser at Nordic Energy Research, defended her PhD on consumer engagement in energy markets – its role, development, and impact on network tariffs and customer service.

In her thesis, Maj has investigated the extent to which Danish consumers want to engage with their electricity company. Among other things, the project provides insight into our response to shifting electricity prices and how willing we are to change our consumption habits and be flexible in our electricity consumption.

It is difficult to find a topic that has received more attention in recent months. We check apps. We get up in the middle of the night to start the washing machine. We turn off the switches so that our television is not on standby and turn down the heat, even though the thermostat shows minus degrees. Many of us feel the energy crisis in the form of bigger bills, and it shapes our behavior and fills the conversations over lunch tables, at the local grocery store, and in the media.

The situation was quite different when Maj Dang Trong started her PhD project at the Department of Sociology, Environmental and Business Economics at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU). Most consumers took electricity for granted. It was something most of us only thought of when the power occasionally went out and the house suddenly fell into darkness, for example, on Christmas Eve when many Danish people roast the duck in the oven at the same time.

That is why Maj set out to create a greater understanding of the Danish consumers’ relationship and attitude towards their electricity company – knowledge that suddenly takes on a completely new meaning under the current energy crisis.

Read the article “Electricity customers need to look over the hedge to understand tariffs“, published by Green Power Denmark.

Consumer interviews

Maj Dang Trong was challenged by one of the opponents about her use of three different interview techniques. Neither the focus group interviews of households nor the in-depth interview of owners of electric vehicles or the interview with distribution companies were statistically representative of the national population. This problem about generalization and purposeful sampling methods was also an issue challenged in the analysis of the questionnaire of fairness perception of electricity prices. At the time of writing the thesis, the selection of so-called “engaged consumers” was especially important: Who was supposed to reflect on new electricity tariff reforms other than consumer representatives in consumer owned distribution companies and members of energy organizations? Would the PhD student have chosen other selection methods today? Yes, she would maybe have increased the target population to include participants in the interviews who showed to be relatively more engaged, such as EV owners and young people who recently and for the first time have moved into their own apartment. In any case, a national study should not have any budget restrictions – and the questions in the questionnaire may need more explanation. Even though people are more engaged in electricity prices, they do not necessary reflect on different elements of the total electricity price.

The second opponent asked the PhD student if she believed that the household consumer was able to provide sufficient flexibility needed for the balancing and supporting of a power system dominated by fluctuation wind power production? This issue was not the main topic of the thesis, but the interviewees in distributions companies emphasised the need for so-called Explicit Demand-side Flexibility. This kind of flexibility is committed, dispatchable flexibility that can be traded (similar to generation flexibility) on the different energy markets (wholesale, balancing, system support, and reserves markets). This is usually facilitated and managed by an aggregator that can be an independent service provider or a supplier. Today, residential customers are not allowed to or capable of providing “reliable” flexibility. For households, flexibility needs to reflect in their everyday rhythm and practices, where implicit demand-side flexibility must be activated by moving (shifting) or reducing the electricity needs.

Consumer involvement

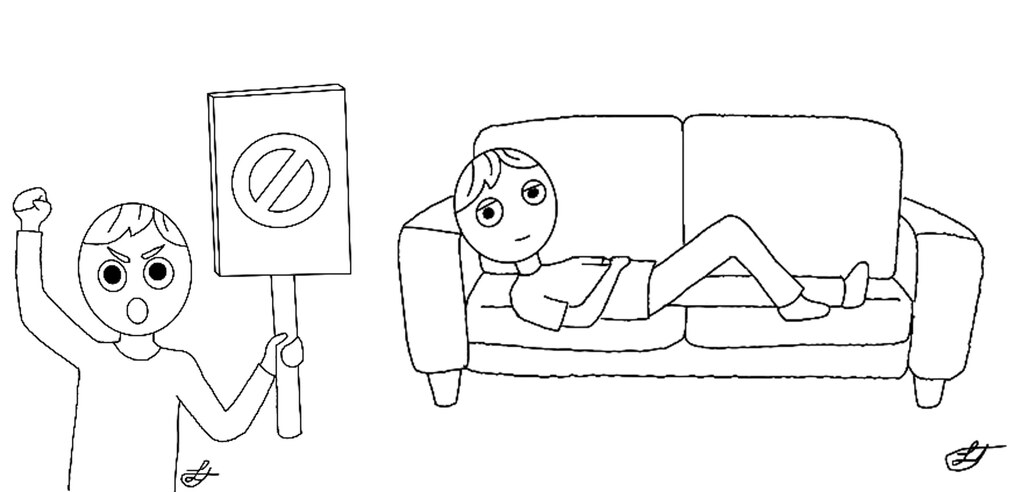

The defense ended with a discussion on the need for (further) consumer involvement from the electricty distribution companies. The question from the last opponent clearly showed that he hardly distinguished between his energy trader and his distribution network company. He had recently contacted his retailer and was surprised by the lack of customer support and staff’s ability to explain his electricity bill to him. Did the PhD student have som advice for him? The answer might be: Do not give up – continue you effort until you receive a satisfying answer. We know, at one extreme, that consumers actively choose to protest, but at the other extreme, that consumers actively choose that they would rather stay on their sofa.

In addition, there are people who experience misrecognition and people who do not always have the mental capabilities to experience misrecognition or to understand electricity reforms appropriately. People can be unable to react on time varying prices – or not capable of being flexible in their use of electricity.

Concluding remarks

Maj concludes by linking her thesis to present conflicts. Europe is currently facing dramatically increased energy prices, and in the light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the uncertainty of supply is exacerbating the problem. The consumer perception on what is “overall” a fair electricity price (including distribution network tariffs) is more relevant than ever. The thesis may reflect history and we may see more people to whom the “reaction – action” implies more active choices in their energy use and more skepticism toward their electricity companies (distribution companies or not).

Acknowledgements from Maj

In the spring of 2018, I met Lars Bonderup Bjørn at Danish Energy Industry’s annual energy conference. At the time, he was a new face in the energy industry, the new CEO of the electricity company EWII. He was to succeed the controversial director who had held the position from long before the electricity sector reform took place. Bonderup Bjørn was enthusiastic about my idea of writing an account in the form of a PhD thesis on the Danish electricity sector from the perspective of the electricity consumer. I am very grateful that EWII and SDU Campus Esbjerg decided to co-finance my PhD.

I am deeply grateful to my supervisor, Associate Professor Yingkui Yang, who has been supporting me all along my study, even when times have been tough. Also, I appreciate the feedback from colleagues inside and outside SDU such as from CBS and the University of Oslo, including the host for my external stay at the Frisch Centre for Economic Research in Norway.

I want to thank the management and staff at the distribution grid company TREFOR (owned by EWII), and at RADIUS Elnet who have actively contributed with interviews about their company and consumer activities. Not least Knud Pedersen, Mads Paabøl, Nan Kofoed (RADIUS), and Charles Nielsen (TREFOR), who have provided me with valuable comments and insight, which would have been impossible to gain without their contribution.

Thank you to all individuals and actors who have set aside time to participate in discussion forums, especially to Martin Salamon from the Danish Consumer Council (today the Energy Agency), Ilyas Dogru from FDM, Jesper Tornbjerg from the industry association Dansk Energi (name changed to Green Power Denmark), Jeannette Møller Jørgensen and Karsten Feddersen from Energinet, Lars Nielsen from the Danish Energy Agency, and Lene Holten Petersen from Forsyningstilsynet. They have all been active professional discussion partners and guided me to their many colleagues who have continuously given feedback on and participated in discussions about the project’s analyses and themes. Nor can I leave out Jørn Limann, who has been an independent “outsider” who helped shedding light on particularly controversial themes, and my highly skilled and former Danish teacher, Egon Poulsen, who has made comments and been my professional language editor in the final process on the work with questionnaires.

I want to thank all 40 participants in my focus groups/interviews, the three owners of an electric vehicle, and the two participant with photovoltaics installed on their roofs. All of you were open-minded and shared your attitudes and experiences with me on energy sector topics that by many are considered complex at the time of doing the thesis, which was not the typical discussion theme at home.